Could you tell me a little bit about yourself and your research interests?

My research revolves around modernism and post-1945 literature, and the essays and books that I have published on Beckett’s work explore its relation to politics, its historical dimensions, and its Irish and European influences. I have been working in the Department of English at the University of York for over ten years.

How did you first encounter Samuel Beckett’s writing?

I must have been about fifteen, I think, when I first heard about Beckett. A friend of mine told me about a play that she had seen in which two actors were trapped in rubbish bins, and I was intrigued! Soon after I came across copies of the early absurdist plays, in the lovely Editions de Minuit versions. I was particularly struck by Oh les beaux jours, with its memorable cover featuring Madeleine Renaud stoically holding her umbrella.

It seemed to me remarkable that a whole play could be made to unfold from that situation, from that image. The author was of no concern to me then, but from that first reading I recall being convinced that the work dealt with colonialism and with colonial wars, and I remember seeing a very literal political dimension within it. The French texts have a peculiar texture; they refract much of what is unsaid about colonial history, and much of what is culturally unsayable about historical injustice, and I was sensitive to that. These were powerful impressions, which stayed with me thereafter. When I began to study Beckett’s work properly, many years later, I did so in light of its Irish literary and historical contexts, and my first monograph was a reappraisal of Beckett’s relation to Ireland. For me, the work is never abstract: it is inseparable from war memory and from the long colonial histories that it invokes. In a sense, this new book was a return to my first impressions: when I started researching, I worked on what is now the final chapter on Beckett and the Algerian War of Independence.

It seemed to me remarkable that a whole play could be made to unfold from that situation, from that image. The author was of no concern to me then, but from that first reading I recall being convinced that the work dealt with colonialism and with colonial wars, and I remember seeing a very literal political dimension within it. The French texts have a peculiar texture; they refract much of what is unsaid about colonial history, and much of what is culturally unsayable about historical injustice, and I was sensitive to that. These were powerful impressions, which stayed with me thereafter. When I began to study Beckett’s work properly, many years later, I did so in light of its Irish literary and historical contexts, and my first monograph was a reappraisal of Beckett’s relation to Ireland. For me, the work is never abstract: it is inseparable from war memory and from the long colonial histories that it invokes. In a sense, this new book was a return to my first impressions: when I started researching, I worked on what is now the final chapter on Beckett and the Algerian War of Independence.

Some people think of Beckett as the author of apolitical works set in hermetically-sealed environments. In what ways do you think your book unsettles or challenges this image?

The view of Beckett as an apolitical author is very deeply enshrined; I would say that this is how the vast majority of people think of Beckett, rather than just some. Distinctive reading habits have formed around Beckett’s work: his writing has always posed formidable challenges to interpretation, and the close reading that it necessitates has an unusual intensity – an intensity that encourages the perception that its political undertones are irrelevant, and that its intellectual and factual moorings are of marginal significance. Beckett is read as a metaphysical writer by default; as someone who was preoccupied about pure philosophical problems, and had little interest in what was taking place around him. In hindsight, now that the field is really shifting, it is amazing to see the persistence with which these assumptions about Beckett have been upheld; when they have been questioned, the questioning has been met with strong resistance, confined to the margins of critical debate, or remained fairly light-touch. Fields of research dealing with other major twentieth-century authors have evolved differently and haven’t made such assumptions quite as forcefully.

“The Beckett that I present is a writer deeply interested in politics, who is working in a densely politicised world. In my view, the political Beckett is a much more compelling figure than the lonely hermit concerned about the nature of being.”

My book is about unsettling this image, and it unsettles it in different ways. The Beckett that I present is a writer deeply interested in politics, who is working in a densely politicised world. In my view, the political Beckett is a much more compelling figure than the lonely hermit concerned about the nature of being. The great difficulty, of course, when it comes to connecting Beckett’s writing to political history, is that the work invokes but does not represent directly. For that reason, my book seeks to reconcile different traditions of scholarship oriented towards historical, theoretical and aesthetic questions. Framed in that way, a dialogue between these different traditions of interpretation becomes possible, and that dialogue is the way forward in my view.

What is at stake in countering received wisdoms about Beckett’s political disaffection is a much broader question about how literature functions within history: the relation between literature and politics is always complicated, particularly in the twentieth century. The belief that literature can or should be divorced from politics is one that I don’t ascribe to. In my view, the consensus around Beckett as apolitical at best and disaffected at worst is like any other powerful consensus around literary history, in that it has articulated itself in spite of abundant evidence to the contrary, against many other counter-currents.

Previously, when critics have looked at Beckett’s relation to politics, they have mostly discussed his involvement in the French Resistance during the Second World War, but in my view his resistance work was only the tip of the iceberg. He had other political commitments too, and I show that he knew much about the political work of many groups and individuals – about the ANC in South Africa, the British and Irish anti-apartheid movements, the Black Panthers and political dissenters imprisoned by the Soviet regime in Eastern Europe and Russia, for example. He signed numerous petitions in defense of other writers, artists and editors over the course of his career, while backing campaigns against censorship and international human rights movements. These petitions had not been discussed before, largely because Beckett’s political work was done behind the scenes, and I believe that the critical volume of petitions that I document in the book changes the equation. I should perhaps clarify that the kind of petition that I discuss has nothing to do with contemporary online petitions: these were politically significant documents that had a different profile, in which each signature mattered and could have consequences.

Previously, when critics have looked at Beckett’s relation to politics, they have mostly discussed his involvement in the French Resistance during the Second World War, but in my view his resistance work was only the tip of the iceberg. He had other political commitments too, and I show that he knew much about the political work of many groups and individuals – about the ANC in South Africa, the British and Irish anti-apartheid movements, the Black Panthers and political dissenters imprisoned by the Soviet regime in Eastern Europe and Russia, for example. He signed numerous petitions in defense of other writers, artists and editors over the course of his career, while backing campaigns against censorship and international human rights movements. These petitions had not been discussed before, largely because Beckett’s political work was done behind the scenes, and I believe that the critical volume of petitions that I document in the book changes the equation. I should perhaps clarify that the kind of petition that I discuss has nothing to do with contemporary online petitions: these were politically significant documents that had a different profile, in which each signature mattered and could have consequences.

“He was knowledgeable about the long history of colonialism, the long history of Europe, the workings of political propaganda and the ideologies of far-right movements. He wasn’t politicised in the usual ways – he wasn’t a member of a political party, for example – but he sustained different kinds of political commitments, like many other writers of his generation, and was broadly committed to a liberal left agenda, particularly in his late career.”

As I was researching the book, I became particularly interested in documenting Beckett’s networks in Ireland, Britain, France and elsewhere, and in showing how his professional career was supported and sometimes made possible by these networks. He was a well-connected artist, animated by a great curiosity, and there are fewer degrees of separation than we often think between him and the more openly politicised artists and thinkers of his time. He was knowledgeable about the long history of colonialism, the long history of Europe, the workings of political propaganda and the ideologies of far-right movements. He wasn’t politicised in the usual ways – he wasn’t a member of a political party, for example – but he sustained different kinds of political commitments, like many other writers of his generation, and was broadly committed to a liberal left agenda, particularly in his late career. Some of his most important friendships were cemented by shared beliefs in the politically transformative power of literature. His close friends and collaborators sometimes paid a high price for their political activities –

Nancy Cunard and his French editor Jérôme Lindon come to mind in this respect. His friends also included figures who stood on the other side of the political fence, particularly during the Second World War. For his part, Beckett had a strong interest in the politics of the left and in the radical left; this interest permeates many facets of his work, and many of the factual details that are invoked in his texts. When he translated texts by other authors, his translation practice was also unusually politicised. He did much rewriting when he worked as a translator for UNESCO after the Second World War, when he collaborated with Octavio Paz on an anthology of Mexican poetry, and when he contributed to an anthology by Nancy Cunard that brought together texts by black authors and reflections on imperialism, segregation and colonial exploitation. What Beckett brought to these works were political insights as well as translations; that much is clear from the content of his translations.

What is the significance of the title, Beckett’s Political Imagination?

The title is a challenge to established ways of reading Beckett: Beckett is commonly thought of as someone who had a brilliant yet deeply abstract and decontextualised way of thinking about representation. The book demonstrates that his writerly imagination was political and politicised. It relates how Beckett responded to the events taking place around him in his writing, and it shows that political history is reimagined in his work in ways that are sometimes deeply idiosyncratic, and at other times sharply attuned to the debates taking place around him. Of course, his work deals with ideas that are not easily compatible with political writing: his texts don’t offer any certainties or clear aspirations, but deal with uncertainty, with exile, with various forms of displacement and deferment. We can’t expect to see directly identifiable, unambiguous representations of real events in Beckett. What we get are evocations, layers, suggestions, echoes, cultural ciphers, lone allusions. So, as such, his writing doesn’t conform with what is normally expected of openly politicised literature. But there is no doubt that his work has spoken to, and continues to speak to, conflict and suffering in ways that other texts by other writers do not. The key themes in his writing, when we think about it, are violence, suffering, exploitation, dispossession, torture and internment. These are politically significant and politically profound themes.

“The key themes in his writing, when we think about it, are violence, suffering, exploitation, dispossession, torture and internment. These are politically significant and politically profound themes.”

How do you think the political and cultural context of Beckett’s time shape his manuscripts and published texts?

Many of Beckett’s texts have connections to, and can be related to, situations and events that he experienced directly over the course of his life, in Ireland, in Germany, in France and elsewhere. From the manner in which he wrote, it is clear that he tried not to write directly about specific events, but that the political tensions that he witnessed frequently inspired him to write in the first place. So, in a sense, he often wrote against his own political sensibilities. There are some interesting manuscripts that attempt to deal with specific political and economic contexts, in Ireland during the 1930s or in France in the aftermath of the Second World War and during the Algerian war of independence, but these were discarded, abandoned or altered beyond recognition. It is important, I think, to pay heed to the work’s capacity to askdifficult questions about its own connections to the contexts in which it was composed, and about the remit of representation more broadly. Beckett, for his part, had a very strong sense that his own political remit as a writer was limited, by virtue of the fact that he was an artist, not a political activist. Yet over the course of his career he witnessed many of the events that shaped the modern history of Ireland, Germany, France, and Europe as we know it. He knew what war and conflict really meant, and he was scarred by some of his experiences. He was deeply interested in those moments when the set course of history is overturned. But the life is one thing, of course, and the work is another. The work is not representational in the usual sense. The work is plural, and deals with many pasts and many presents at the same time. The contexts to which it responds are plural, shifting, simultaneous. The work’s cross-cultural and cross-linguistic dimensions are of crucial importance and are always challenging.

“The work is not representational in the usual sense. The work is plural, and deals with many pasts and many presents at the same time. The contexts to which it responds are plural, shifting, simultaneous. The work’s cross-cultural and cross-linguistic dimensions are of crucial importance and are always challenging.”

There are different ways of contextualising an author’s work: it is possible to sketch out broad historical lines and frame a body of texts in that way, and this can be done relatively easily, but context can remain distant and the links can remain speculative and tenuous. I tried to go beyond that: I tried to bring political history as close as possible to the work. I wanted to join the dots, to return fromhistorical facts back to Beckett, to the political worlds in which he was immersed, and to his own reimagining of political history. This close historical work was a necessity: the political contexts to which Beckett’s writing responds are not necessarily well known to us today, and multiple forms of war memory – notably, the memory of the Algerian war – leave traces in the texts that are delicate, and difficult to fathom without careful contextualisation.

Could you tell me a little bit about your research for the project?

The research and writing took over ten years, which seems like a very long time (and felt like a long time!) but this was unavoidable: big monographs require this kind of slow research, and the pace at which they progress is often opposed to the pace of contemporary academia. The book was written in small increments, whenever it was possible to write: my job keeps me busy, and I did many other things during that time as well. It began as a project with a strong theoretical dimension, but as time went by the theoretical arguments lost prominence and biographical and historical details expanded. What was most time-consuming in terms of the research was honing the book’s overall frame, and collecting all the documents and evidence demonstrating Beckett’s close interest in politics and political activism, because much of this came from newspaper articles and microfilms that are not indexed or easily available. The anecdotes and episodes related in the book emerged gradually. I visited archives in Ireland, in France, in Britain and in the US – the Beckett archives are surprisingly scattered – and I spent as much time in research libraries as I could. When it came to writing, some sections took longer than others: the chapter on the Algerian war, for example, took ten years to reach its final form. Crafting a narrative for the first chapter, which deals with the 1930s and Beckett’s efforts as a historical writer and political essayist, also took years. The chapter on testimony and the aftermaths of the Second World War was challenging to write, for other reasons: it deals with materials that affected me deeply.

Did you encounter any shocks or surprises during the course of researching the book?

The most unlikely find was probably the detailed map of the Santé prison that I cite in the final chapter (in 1960, Beckett moved to a flat – where he remained thereafter – situated next to the prison). Maps of high-security prisons are not in the public domain, for obvious reasons, but I found one by chance, buried in the Law section at the University of Caen library, when I was working at the IMEC.

“Petition-signing is one of the most common measures of political activity in the twentieth century, and Beckett was said to have signed either none, or just one, or else a handful – and these were mostly rumours which came without footnotes or references.”

Beyond that, yes, shocks and surprises were frequent, particularly when I started to accumulate a significant number of petitions bearing Beckett’s signature. Petition-signing is one of the most common measures of political activity in the twentieth century, and Beckett was said to have signed either none, or just one, or else a handful – and these were mostly rumours which came without footnotes or references. So I had to do a lot of chasing, and I had to go about it in imaginative and counter-intuitive ways sometimes. It proved to be a strange process: after a while I began to develop a good sense of the kinds of documents that he may have endorsed, and whenever I had time to look I found more petitions bearing his signature. Once I realised that he began to sign petitions around the time he decided to become a professional writer (the first was an appeal issued by Nancy Cunard in defense of the Scottsboro Boys), the trajectory became clearer, and the task became easier. Many of the petitions that he signed later, between the late 1960s and the late 1990s, were published in national newspapers that had a large circulation, and were also supported by artists known for their political activities. But Beckett’s contributions went by and large without comment. It is astonishing, I think, that such a well-known figure could sign so many public petitions and be so widely perceived as apolitical.

How can Beckett’s political engagement help us to address our own cultural and historical moment?

The situations that are represented in Beckett’s texts can seem far removed from the world we know, but they are also dimly recognisable; his plays, for example, evoke situations of hardship that many people have faced over the course of history. His work also offers wonderful insights into memory and the importance of courage and solidarity. It is no wonder that in some parts of the globe Beckett continues to be seen as a writer who sheds light on the world’s cruelties and ironies: Waiting for Godot, notably, is consistently received as a text that has a political weight. There have been press reports in the past few years commenting on the significance of Beckett’s writing for people in Syria, or on the West Bank, or in cities devastated by war or natural catastrophe elsewhere. People across the world continue to read Beckett and find strength and solace in his writing. We can also look to him, of course, as an interesting model for what political principle can look like: he occasionally took real risks, and privileged action over words. But there is a big difference between the world in which Beckett lived and the world that most of us reading Beckett, in the West, know today. Personally, I don’t turn to literature or to modernism when I want to think about the times we are living in – I look elsewhere – but I wouldn’t dissuade anyone from doing so either: I can understand the many people who find in Beckett an evocative mirror for their own political angst. The work is full of fabulous lines and aphorisms that acquire striking resonances once they are pitted against real events, real situations of injustice and suffering.

“The work is full of fabulous lines and aphorisms that acquire striking resonances once they are pitted against real events, real situations of injustice and suffering.”

Do you have a favourite Beckett text?

I enjoy returning to the late plays – Ohio Impromptu and the plays for television – as well as the prose fragments – Lessness, for example. These are endlessly fascinating texts, which just about bear to be read and looked at. In general, I see new things in the work every time I return to it, and that’s largely because I’ve had such wonderful students over the years.

What’s next for you?

Other horizons… Right now, I am writing a piece on prison writing during the Algerian war, and thinking about radio.

Beckett’s Political Imagination is published by Cambridge University Press (£31.99; US $39.99).

About the Author

Emilie Morin, a Senior Lecturer in English at the University of York, is the author of Beckett’s Political Imagination (2017) and Samuel Beckett and the Problem of Irishness(2009), and has co-edited Theatre and Human Rights after 1945: Things Unspeakable (2015) and Theatre and Ghosts: Materiality, Performance and Modernity (2014).

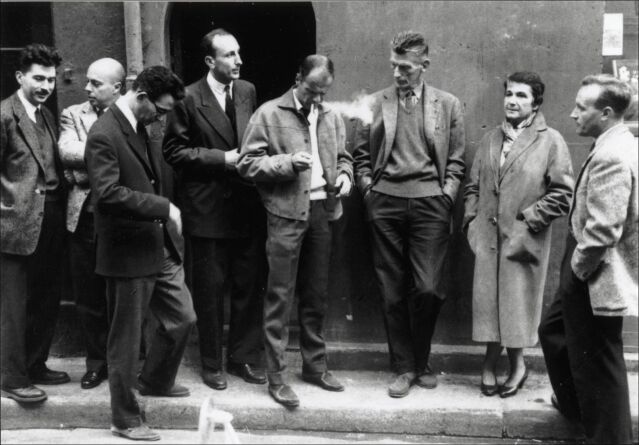

Masthead image: © Mario Dondero/Leemage.

This picture, the symbol of the “nouveau Roman” is taken by Mario Dondero. It’ll be great if you can put the copyright © Mario Dondero/Leemage.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I have updated the interview with the appropriate accreditation.

LikeLike