Feuilleton. Traditionally, a ‘feuilleton’ is a portion at the bottom of a French newspaper that is kept free for light literature, criticism, and commentary. It derives from the word ‘feuille’, meaning ‘leaf’. By its very nature, the feuilleton is marginal and fragmentary. For the early twentieth-century author Robert Walser, this became an ideal medium for his wandering and ephemeral style.

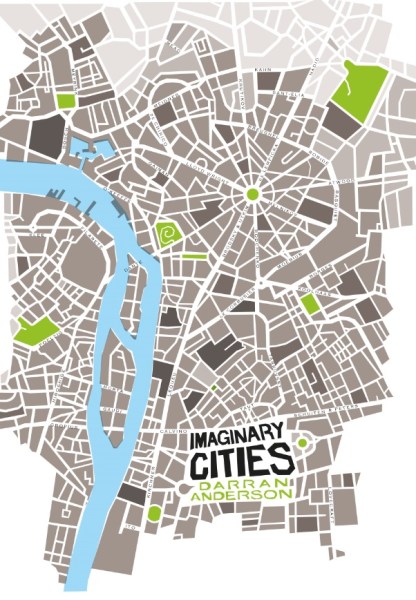

The NYRB’s wonderful new collection of the Swiss writer’s short texts, entitled Girlfriends, Ghosts, and Other Stories, allows us to leaf through a life of extraordinary writing. The German writer and academic W. G. Sebald, using Walser’s own words, described him as a ‘clairvoyant of the small’, a writer of prose ‘at odds with the demands of high culture’. Tom Whalen’s afterword to the NYRB volume echoes this sentiment, recognizing in Walser a sensibility of ‘sovereign insignificance’. Whalen continues: ‘For the fueilletonist anything can be an occasion for a prose piece: a walk in the mountains, a new hairstyle, an old fountain, shopwindows, a kitten, a carousel, a Parisian newspaper’. As Walser drifts aimlessly through the modern European city, we share his curiosity and wonder at the small details of this strange and peculiar life.

(more…)