What kind of academic journal is Barthes Studies?

Barthes Studies is an open-access online journal dedicated to the work of influential French literary and cultural theorist and critic Roland Barthes. It’s the only such journal in English (although there is an older French equivalent, the Revue Roland Barthes), and it was founded by Neil Badmington in 2015 with an issue that marked the centenary of Barthes’ birth. It’s interdisciplinary, has published articles by those working in French studies, English studies, literary theory, and cultural theory, and is open to those working in any area that has to do with Barthes. Because of the breadth and variety of his interests and writings, this is a very wide remit indeed!

What inspired you to oversee an issue devoted to the subject of poetry?

I think a few years ago, many people who are interested in Barthes, particularly in the UK, were seeing that there was a gap: it was commonly assumed that Barthes had something to say that was of relevance to poetry, and perhaps experimental poetry in particular, but why had so little been written about Barthes and poetry? I looked at a lot of books about poetry and found that in the index they would have one or two references to Barthes, but that these would lead to passing references to his most famous ‘The Death of the Author’ – an essay we assumed all the poets and poetry critics were familiar with, but nobody wanted to seem to talk about why, or how they got that way. When I started my PhD at Cardiff’ in 2013, I was hoping to fill this gap.

“[I]t was commonly assumed that Barthes had something to say that was of relevance to poetry, and perhaps experimental poetry in particular, but why had so little been written about Barthes and poetry?”

I was already working on Barthes Studies as Reviews Editor when Neil and I came up with the idea of making Volume 2 a special issue on poetry. I was invited to speak at the ‘Barthes and Poetry’ Conference organised by Andy Stafford, Nigel Saint, Richard Hibbitt, and Claire Lozier at Leeds University in March 2015, and that conference became the intellectual basis for the issue, so I owe a great deal to them as well. I think we have started to do some of the thinking that will bridge the gaps between Barthes and poetry, and orient it as a subject of inquiry for many more readers and scholars to come.

In what ways can Barthes inform the way we read, write, or understand poetry today?

In many ways, Barthes doesn’t like poetry; depending on which of our special issue’s contributors you ask, he may even ‘hate’ or ‘fear’ it, and avoids talking about it where possible. But one of the major insights we draw from Barthes is that writing is not the sole product of a single writer. Rather, it is co-produced by its readers, and we have to engage enthusiastically in that co-production if we want to learn new things about poetry from Barthes.

Most of the critical material in the issue was written, or at least initial conceived of, before the big political events of 2016, but my editorial, ‘The Terrible Power of Language’, was written in amongst them. Although many people think of Barthes as an apolitical writer, in his autobiography Roland Barthes (1975), he explained why: when we allow politics to be the ‘fundamental science of the real’, it ‘checkmates’ language. Talk all you want, someone might say to the theorist or poet, but this is the real world. But as Barthes points out, it isn’t, and politics is eventually evacuated of meaning, and becomes ‘Prattle’. Poetry’s role is to smash this kind of language by refusing to use it.

However, when we give up on easy, meaningless speech, our writing becomes ‘unreadable’. This charge, levelled at all kinds of poetry but particularly at experimental writing, was also familiar to Barthes, and in a 1969 essay only recently published for the first time in English, ‘Ten Reasons to Write’, he defended the ‘unreadable’, saying: ‘It is revolutionary because it is associated not with a different political regime but with “another way of feeling, another way of thinking”.’ Being defiantly unreadable – or, as Barthes also calls it in that essay, ‘counter-readable’ – in an age that gives unprecedented political power to Prattle is perhaps poetry’s most important job. Does a poem effect change or resist violence? Maybe not. But it offers some thinking- and feeling-space to help us do so.

How do you think poetry and theory, or philosophy more broadly, inform each other?

It’s very hard to generalise because there is so much being written which is classified as “poetry”. Some poets have very little interest in theory, preferring to draw instead on nature, history, politics, or other aspects of the culture, and to define formal elements of their practice against . However, as a practicing poet and editor of the poetry journal Zarf, I see how much theory informs the intellectual life of many poets, particularly those working in experimental modes. They rightly identify theory of all kinds as a rich resource to incorporate into writing that wants to say something in a new way.

“[…] as a practicing poet and editor of the poetry journal Zarf, I see how much theory informs the intellectual life of many poets, particularly those working in experimental modes. They rightly identify theory of all kinds as a rich resource to incorporate into writing that wants to say something in a new way.”

There are also perhaps some kinds of thinking that can only be done in poetry, movements and connections that can’t be made through the kind of argumentation that philosophical thought demands but which can be done with a command of language as a set of flexible, breakable forms. Such texts bear the marks of some nuanced theoretical or philosophical thinking, but they don’t demand it of their readers: in fact, what they require is that the reader be willing to do some thinking that is non-theoretical, un-analytical, and let meanings come together in what may seem like ‘unreasonable’ ways.

What’s next for you?

I’m currently working on a monograph based on my PhD thesis on how English-language poets in the 1970s and 80s responded to Barthes. In this I want to explore some of the things that have not yet been said about Barthes – how does engagement with a radically impersonal doctrine like ‘The Death of the Author’ mean when the function of writing – particularly poetry and other modes of writing on the edge – is to bolster an experience that is under threat of erasure? I want to work with Barthes to produce a reading of him that makes him more valuable than ever to poets and readers of poetry.

My next project, which I’m also in the early stages of planning and researching, will be about catachresis, the rhetorical trope of using the wrong words. How do forms of discourse which re-appropriate language, like poetry, use this ‘wrongness’ or ‘slippage’ to have the effect they do?

The special issue of Barthes Studies is freely-available from Cardiff University.

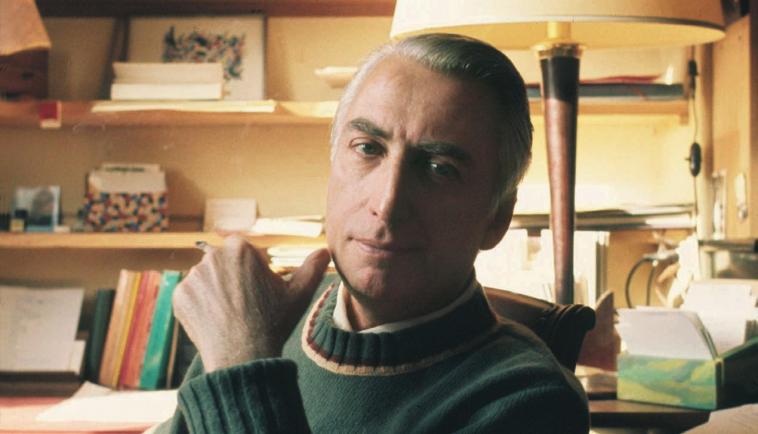

About the Editor

Calum Gardner is a poet, editor, and poetry scholar living in Glasgow, Scotland. Calum is working on a book about poets’ responses to the theory of Roland Barthes, and edits Zarf poetry magazine at zarfpoetry.tumblr.com. You can follow Zarf on Twitter @zarfpoetry.

“There are also perhaps some kinds of thinking that can only be done in poetry, movements and connections that can’t be made through the kind of argumentation that philosophical thought demands but which can be done with a command of language as a set of flexible, breakable forms.”

A most interesting conversation, especially in the light of the fact that I (and many of the people I know) am drawn to poetry more and more in the light of the socio-political turns of recent months. Thank you.

LikeLike